In the face of looming cutbacks, it’s time for the Department of Conservation to show the NZ public where their nearly $800m dollar budget is spent – and cast some sunlight on their ‘ghost costs’ and accounting practices

Opinion: This year the Department of Conservation faces a 7 percent budget cut, on top of many millions of dollars of deferred maintenance. The budget cut comes at a time when tourism is approaching pre-Covid levels, with a return to the overflowing toilets, carparks and crowds that defined the pre-Covid era.

Faced with this crunch, which way will the department turn? Will it funnel the remaining money and services into essentially subsiding big tourism, with small communities and regional New Zealand losing out, or will it take a pause, reflect on the huge success that local communities have had in managing recreation and biodiversity themselves, and chart a different course?

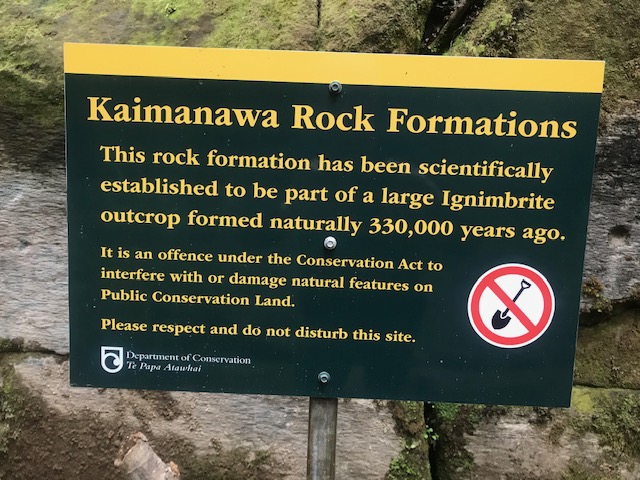

Over the past decade and a half, New Zealand has seen a quiet revolution in conservation and recreation – a positive and empowering exercise that has seen the bulk of our smaller backcountry huts, and an increasing proportion of our tracks, in better condition than they have ever been.

The work even extended to a few critical bridges. Local communities have stepped in where DoC has withdrawn to focus on tourism, reopening tracks the department can’t engage on. Of its around 900 huts – especially of the 450 or so ex Forest Service huts, which remain the core of the network and the most cherished by outdoor folk – the vast bulk of the deferred maintenance burden has been resolved.

Having loyally served the public for the past 50 years, these huts are now good for at least the next 50. This maintenance and upgrade exercise occurred as trampers, hunters, kayakers, mountain-bikers and skiers empowered themselves and took on the task of looking after these places themselves. It was primarily funded by the Backcountry Trust, with support from the remaining DoC regional staff and some contractors, cutting layers of unnecessary red tape in the process.

And the cost? About $6 million over a decade. This is the same amount of revenue DoC receives from annual hut pass holders during the same timeframe. Compare this to its annual recreation budget of $200m or over a billion dollars across 10 years.

On these proven figures, there is no funding crisis nor maintenance issue in recreation, begging the question of where DoC’s money actually goes. For at least half the network, there’s already a proven funding mechanism and large network of people looking after it, but it requires the department’s head office to loosen the reins.

DoC claims to operate a world-class asset management and accounting system for huts and tracks, but the public does not have any transparency to see where and how the money is spent. There has been no critical analysis of their spending, as the numbers simply aren’t available at the detail required.

For instance, DoC is required to spend at least $42m a year on capital asset charges for huts and tracks, with depreciation on top of this again – far more than they actually spend on maintenance – which goes back to the Crown.

There’s no guarantee that all of the community-led maintenance and upgrading work has even been recorded on a spreadsheet, because if it was, DoC would face an even bigger bill.

These are self-imposed restrictions, as Treasury has workarounds that the department seemingly won’t use. Subtract staff costs, capital charges, and depreciation from its recreation budget and there might be just enough left over to maintain tourism tracks. There’s nothing left over for Kiwis in the backcountry, with most DoC regions having essentially zero discretionary funds.

DoC receives a proportion of the International Visitor Levy, $35 paid by most tourists entering New Zealand. However, what isn’t clear, especially in the light of overflowing toilets at Aoraki Mt Cook, is how much of it leaves Wellington and actually makes it to the places it needs to be used.

If central government and the department could provide certainty that this money actually gets spent appropriately and makes it to the tourism hotspots, then the charge could easily be doubled, potentially fixing some of the acute day-to-day issues DoC faces.

Furthermore, where there are actual deferred maintenance issues – usually on the front country tracks, bigger huts, and Great Walks – DoC’s internal rules and practices significantly inflate the actual costs. However, as cutbacks loom, these ‘ghost costs’ stemming from potentially unfit accounting practices risk cutbacks in all the wrong areas.

The public desperately needs DoC to open the books and open its eyes to alternative solutions. The department has the highest (nominal) budget it has ever received, but yet it is getting less done in the field. It is no coincidence that it also has a high head count of Wellington head office staff.

For an organisation tasked with maintaining one third of the country, it simply must reorganise itself around delivery on the ground, and if it can’t, get out of the way and enable other more qualified and experienced people to do this task. This applies to biodiversity as much as it does to recreation.

But it is easier to cut back in the regions than it is to cut back in Wellington, and while proven models exist to significantly improve both biodiversity and recreation while at the same time reducing costs, is DoC willing to be clear-eyed and cut inefficiencies? Or simply go for what it perceives to be low-hanging fruit?

The coalition Government appears to support devolution back to local communities, and to support traditional Kiwi pastimes like hunting, fishing, and tramping (which are growing substantially while other pastimes like rugby continue to decline). But also, like most governments before it, prime the tourism pump.

Lurching to privatisation and user-pays may be a tempting option for a new minister and a cost-conscious Government, but why privatise when the country has only just embarked upon the community participation model for the public provision of huts and tracks that has always set the New Zealand mountains apart from those overseas?

This model is a welcome resurgence of the community values that built our nation, a welcome return to the days when people felt less entitled about the state doing everything for them and were prepared to step up and use their skills and time for the public good. This model should be a good fit with the new Government, but if privatisation and divestment are the only options presented by the department to the new minister, the nascent return to a better approach might be lost before it can be properly embedded.

DoC has new management, but the question will be if it is bold enough to adopt a different accounting and management framework, become more field-focused, empower volunteers and the community, and at the same time, restore trust – especially at a local community level.

Outdoor non-government organisations need to be strong enough to hold DoC management to account so we can keep working together to preserve the best backcountry hut and track system in the world.

Above all, it will be interesting to see if new Minister of Conservation Tama Potaka is willing to take the opportunity to embed a far better conservation and recreation system for New Zealand by facilitating those discussions and steering his department.

This year, we find out.

Peter Wilson

Peter Wilson is an independent conservation and recreation planner, former DoC statutory planner and former president of the Federated Mountain Clubs of New Zealand.